Thirty years ago, a NASA scientist, James Hansen, told lawmakers at a Senate hearing that “global warming is now large enough that we can ascribe with a high degree of confidence a cause-and-effect relationship with the greenhouse effect.” He added that there “is only 1 percent chance of accidental warming of this magnitude.”

By that, he meant that humans were responsible.

His testimony made headlines around the United States and the world. But in the time since, greenhouse gas emissions, the global temperature average and cost of climate-related heat, wildfires, droughts, flooding and hurricanes have continued to rise.

This fall, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released an alarming report warning that if emissions continue to rise at their present rate, the atmosphere will warm up by as much as 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) above preindustrial levels by 2040, resulting in the flooding of coastlines, the killing of coral reefs worldwide, and more catastrophic droughts and wildfires.

To avoid this, greenhouse gas emissions would need to fall by nearly half from 2010 levels in the next 12 years and reach a net of zero by 2050. But in the United States, the world’s second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, President Trump continues to question the science of climate change, and his administration is rolling back emissions limits on power plants and fuel economy standards on cars and light trucks, while pushing to accelerate the use of fossil fuels. Other major nations around the world aren’t cutting emissions quickly enough, either... (continues)

PHIL 3340 Environmental Ethics-Supporting the philosophical study of environmental issues at Middle Tennessee State University and beyond...

Saturday, December 29, 2018

Thursday, December 27, 2018

Trump Imperils the Planet

Endangered species, climate change — the administration is taking the country, and the world, backward.

It’s hard to believe but it was only three years ago this month — just after 7 p.m., Paris time, Dec. 12, to be precise — that delegates from more than 190 nations, clapping and cheering, whooping and weeping, rose to celebrate the Paris Agreement — the first genuinely collective response to the mounting threat of global warming. It was a largely aspirational document, without strong legal teeth and achieved only after contentious and exhausting negotiations. But for the first time in climate talks stretching back to 1992, it set forth specific, numerical pledges from each country to reduce emissions so that together they could keep atmospheric temperatures from barreling past a point of no return.

Two weeks ago, delegates met at a follow-up conference in Katowice, Poland, to address procedural questions left unsettled in Paris, including common accounting mechanisms and greater transparency in how countries report their emissions. In this the delegates largely succeeded, giving rise to the hope, as Brad Plumer put it in The Times, that “new rules would help build a virtuous cycle of trust and cooperation among countries, at a time when global politics seems increasingly fractured.”

But otherwise it was a hugely dispiriting event and a fitting coda to one of the most discouraging years in recent memory for anyone who cares about the health of the planet — a year marked by President Trump’s destructive, retrograde policies, by backsliding among big nations, by fresh data showing that carbon dioxide emissions are still going up, by ever more ominous signs (devastating wildfires and floods, frightening scientific reports) of what a future of unchecked greenhouse gas emissions is likely to bring.

The conference itself showcased the very fossil fuels that scientists and most sentient people agree the world must rapidly wean itself from. Poland’s president, Andrzej Duda, set the tone by declaring he had no intention of abandoning coal, which provides nearly four-fifthsof Poland’s electricity. The United States and three other major oil producers — Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Russia — refused to endorse an alarming report issued in October by the United Nations scientific panel on climate change calling for swift reductions in fossil fuel use by 2030 to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, which it said were approaching much faster than anyone had thought... (continues)

Two weeks ago, delegates met at a follow-up conference in Katowice, Poland, to address procedural questions left unsettled in Paris, including common accounting mechanisms and greater transparency in how countries report their emissions. In this the delegates largely succeeded, giving rise to the hope, as Brad Plumer put it in The Times, that “new rules would help build a virtuous cycle of trust and cooperation among countries, at a time when global politics seems increasingly fractured.”

But otherwise it was a hugely dispiriting event and a fitting coda to one of the most discouraging years in recent memory for anyone who cares about the health of the planet — a year marked by President Trump’s destructive, retrograde policies, by backsliding among big nations, by fresh data showing that carbon dioxide emissions are still going up, by ever more ominous signs (devastating wildfires and floods, frightening scientific reports) of what a future of unchecked greenhouse gas emissions is likely to bring.

The conference itself showcased the very fossil fuels that scientists and most sentient people agree the world must rapidly wean itself from. Poland’s president, Andrzej Duda, set the tone by declaring he had no intention of abandoning coal, which provides nearly four-fifthsof Poland’s electricity. The United States and three other major oil producers — Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Russia — refused to endorse an alarming report issued in October by the United Nations scientific panel on climate change calling for swift reductions in fossil fuel use by 2030 to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, which it said were approaching much faster than anyone had thought... (continues)

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

78 Environmental Rules on the Way Out Under Drumpf

Since his first days in office, President Drumpf has made eliminating federal regulations a priority. His administration, with help from Republicans in Congress, has targeted environmental rules it sees as overly burdensome to the fossil fuel industry, including major Obama-era policies aimed at fighting climate change.

A New York Times analysis, based on research from Harvard Law School, Columbia Law School and other sources, counts nearly 80 environmental rules on the way out under Mr. Drumpf. Our list represents two types of policy changes: rules that were officially reversed and rollbacks still in progress. Nearly a dozen more rules – summarized at the bottom of this page – were rolled back and then later reinstated, often following legal challenges... (continues)

==

In just two years, President Drumpf has unleashed a regulatory rollback, lobbied for and cheered on by industry, with little parallel in the past half-century. Mr. Drumpf enthusiastically promotes the changes as creating jobs, freeing business from the shackles of government and helping the economy grow.

The trade-offs, while often out of public view, are real — frighteningly so, for some people — imperiling progress in cleaning up the air we breathe and the water we drink, and in some cases upending the very relationship with the environment around us.

Since Mr. Drumpf took office, his approach on the environment has been to neutralize the most rigorous Obama-era restrictions, nearly 80 of which have been blocked, delayed or targeted for repeal,according to an analysis of data by The New York Times.

With this running start, Mr. Drumpf is already on track to leave an indelible mark on the American landscape, even with a decline in some major pollutants from the ever-shrinking coal industry. While Washington has been consumed by scandals surrounding the president’s top officials on environmental policy — both the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency and the Interior secretary have been driven from his cabinet — Mr. Drumpf’s vision is taking root in places as diverse as rural California, urban Texas, West Virginian coal country and North Dakota’s energy corridor.

While the Obama administration sought to tackle pollution problems in all four states and nationally, Mr. Drumpf’s regulatory ambitions extend beyond Republican distaste for what they considered unilateral overreach by his Democratic predecessor; pursuing them in full force, Mr. Drumpf would shift the debate about the environment sharply in the direction of industry interests, further unraveling what had been, before the Obama administration, a loose bipartisan consensus dating in part to the Nixon administration.

In the words of Walter DeVille, who lives on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota, “This is our reality now.” (continues)

A New York Times analysis, based on research from Harvard Law School, Columbia Law School and other sources, counts nearly 80 environmental rules on the way out under Mr. Drumpf. Our list represents two types of policy changes: rules that were officially reversed and rollbacks still in progress. Nearly a dozen more rules – summarized at the bottom of this page – were rolled back and then later reinstated, often following legal challenges... (continues)

==

‘This is our reality now.’

The trade-offs, while often out of public view, are real — frighteningly so, for some people — imperiling progress in cleaning up the air we breathe and the water we drink, and in some cases upending the very relationship with the environment around us.

Since Mr. Drumpf took office, his approach on the environment has been to neutralize the most rigorous Obama-era restrictions, nearly 80 of which have been blocked, delayed or targeted for repeal,according to an analysis of data by The New York Times.

With this running start, Mr. Drumpf is already on track to leave an indelible mark on the American landscape, even with a decline in some major pollutants from the ever-shrinking coal industry. While Washington has been consumed by scandals surrounding the president’s top officials on environmental policy — both the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency and the Interior secretary have been driven from his cabinet — Mr. Drumpf’s vision is taking root in places as diverse as rural California, urban Texas, West Virginian coal country and North Dakota’s energy corridor.

While the Obama administration sought to tackle pollution problems in all four states and nationally, Mr. Drumpf’s regulatory ambitions extend beyond Republican distaste for what they considered unilateral overreach by his Democratic predecessor; pursuing them in full force, Mr. Drumpf would shift the debate about the environment sharply in the direction of industry interests, further unraveling what had been, before the Obama administration, a loose bipartisan consensus dating in part to the Nixon administration.

In the words of Walter DeVille, who lives on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota, “This is our reality now.” (continues)

Earthrise & environmentalism

Seen from space 50 years ago, Earth appeared as a gift to preserve and cherish. What happened?

The "Earthrise" photograph taken by William Anders on Apollo 8 on Christmas Eve in 1968.CreditNASA

On Christmas Eve 1968, human beings orbited the moon for the first time. News of the feat of NASA’s Apollo 8 mission dominated the front page of The New York Times the next day. Tucked away below the fold was an essay by the poet Archibald MacLeish, a reflection inspired by what he’d seen and heard the night before.

Even after 50 years, his prescient words speak of the humbling image we now had of Earth, an image captured in a photograph that wouldn’t be developed until the astronauts returned: “Earthrise,” taken by William Anders, one of the Apollo crew. In time, both essay and photo merged into an astonishing portrait: the gibbous Earth, radiantly blue, floating in depthless black space over a barren lunar horizon. A humbling image of how small we are — but even more, a breathtaking image of our lovely, fragile, irreplaceable home. The Earth as a treasure. The Earth as oasis.

When the Apollo 8 commander, Frank Borman, addressed Congress upon his return, he called himself an “unlikely poet, or no poet at all” — and quoted MacLeish to convey the impact of what he had seen. “To see the Earth as it truly is,” said the astronaut, quoting the poet, “small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the Earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold — brothers who know now that they are truly brothers.”

The message offered hope in a difficult time. Not far away on that same front page was a sobering report that the Christmas truce in Vietnam had been marred by violence. These were the last days of 1968, a divisive and bloody year. We’d lost Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy that year, gone through a tumultuous election, and continued fighting an unpopular and deadly war.

For MacLeish, these images of Earth from space would help usher in a new era, overturning the old notion of humanity as the center of the universe and the modern view of us humans as little more than “helpless victims of a senseless farce.” Beyond these two extremes, MacLeish suggested, was an image of the planet as a kind of lifeboat, “that tiny raft in the enormous, empty night.”

Commander Borman himself compared Earth to an “aggie,” no doubt recalling playing marbles as a boy, drawing circles in the dirt. The famous “Blue Marble” image — one of the most reproduced photographs in human history — came four years later, from Apollo 17. But for Commander Borman and MacLeish alike, what “Earthrise” revealed wasn’t a marble made vast but a planet made small. A little blue sphere, a child’s precious aggie, floating alone in the abyss.

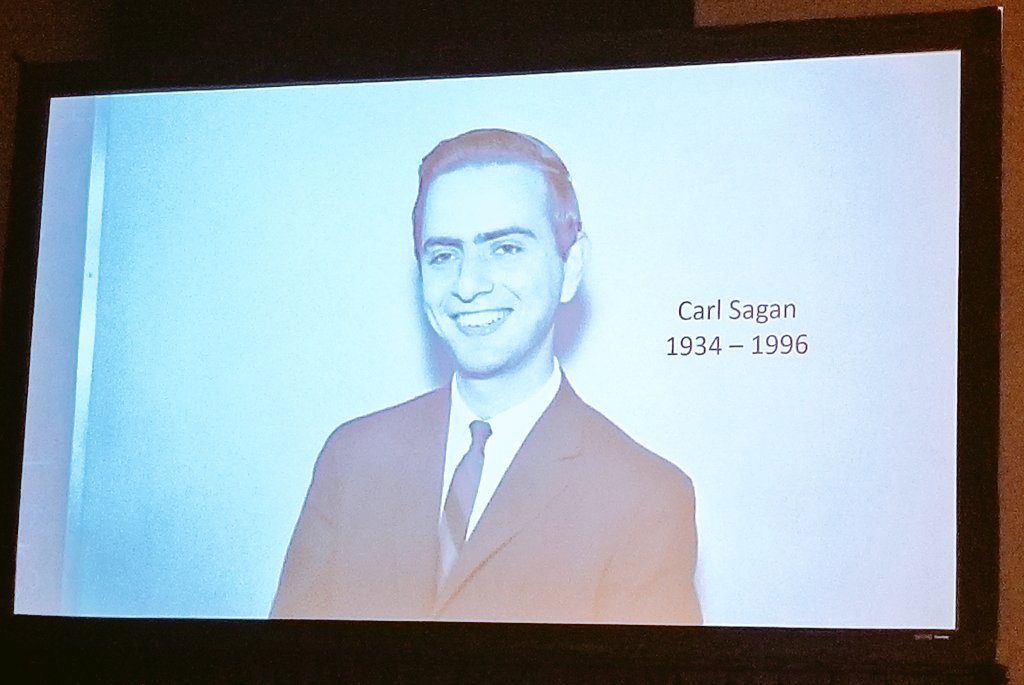

Much later, Carl Sagan would pick up this line of thought in his 1994 book, “Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space,” in which the Earth, as photographed in 1990 from the Voyager 1 from 3.7 billion miles away, became “a mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam.” For Sagan, this new image challenged “the delusion that we have some privileged position in the universe,” and at the same time “underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly and compassionately with one another and to preserve and cherish that pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

Since then, we’ve learned a great deal more. When Voyager 1 took that picture, we weren’t yet sure whether there were any planets at all outside our solar system. But today, largely thanks to space telescopes peering out from Earth’s orbit, we know we look up at night into a galaxy with more planets than stars. We may now perceive, as never before, the Earth’s exquisite rarity and value. We live on a marvel to behold.

We also know how our own DNA links us to one another and to life on our planet in general. We need not imagine ourselves as brothers and sisters, because science tells us that we are one family of life that includes plants, animals, birds, insects, fungi, even bacteria. All of life rides on Earth together.

By the time Sagan delivered his message “to preserve and cherish” our planet, the awareness of our responsibility to care for the Earth had already taken hold. In 2018, it is virtually impossible to see “Earthrise” without thinking of the ways the planet’s biosphere — proportionally as thin as a coat of paint on a classroom globe — is not only fragile but also under sustained attack by human actions. It is hard not to conclude that we have utterly failed to uphold the grave responsibility that the Apollo 8 crew and “Earthrise” delivered to us.

Our precious “raft” is losing members — species are dying — as our climate changes and our planet warms. The very technologies that flung us around the moon and back, the dazzling industrial genius that gave us fossil-fuel-fed transport and electricity, animal agriculture and all the rest, have fundamentally changed our Earth, and they now threaten to cook us into catastrophe. We may be afloat in MacLeish’s “eternal cold,” but what MacLeish couldn’t yet see was how, even then, we were madly stoking the furnace.

It’s all there in “Earthrise,” if we look closely enough. Those spiraling ribbons of clouds foreshadow the extreme weather to come. In the foreground, the gray moon testifies to how unforgiving the laws of nature can be. And behind the camera, so to speak, is the sprawling apparatus of the modern industrial age, spewing an insulating layer of haze around that little blue marble, the only home we’ve ever known.

Today, against the backdrop of our enormous challenge in salvaging the Earth, MacLeish’s message almost seems quaint, if not dated. (He wrote of brothers, no sisters mentioned.) And yet, the poet still has a point. The vision of “Earthrise” is still one of awe and wonder. As we continue to venture out beyond Earth’s orbit, we citizens of Earth can at least hope that we will still be humbled by each new vision of our lonely planet from space.

The "Earthrise" photograph taken by William Anders on Apollo 8 on Christmas Eve in 1968.CreditNASA

On Christmas Eve 1968, human beings orbited the moon for the first time. News of the feat of NASA’s Apollo 8 mission dominated the front page of The New York Times the next day. Tucked away below the fold was an essay by the poet Archibald MacLeish, a reflection inspired by what he’d seen and heard the night before.

Even after 50 years, his prescient words speak of the humbling image we now had of Earth, an image captured in a photograph that wouldn’t be developed until the astronauts returned: “Earthrise,” taken by William Anders, one of the Apollo crew. In time, both essay and photo merged into an astonishing portrait: the gibbous Earth, radiantly blue, floating in depthless black space over a barren lunar horizon. A humbling image of how small we are — but even more, a breathtaking image of our lovely, fragile, irreplaceable home. The Earth as a treasure. The Earth as oasis.

When the Apollo 8 commander, Frank Borman, addressed Congress upon his return, he called himself an “unlikely poet, or no poet at all” — and quoted MacLeish to convey the impact of what he had seen. “To see the Earth as it truly is,” said the astronaut, quoting the poet, “small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the Earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold — brothers who know now that they are truly brothers.”

The message offered hope in a difficult time. Not far away on that same front page was a sobering report that the Christmas truce in Vietnam had been marred by violence. These were the last days of 1968, a divisive and bloody year. We’d lost Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy that year, gone through a tumultuous election, and continued fighting an unpopular and deadly war.

For MacLeish, these images of Earth from space would help usher in a new era, overturning the old notion of humanity as the center of the universe and the modern view of us humans as little more than “helpless victims of a senseless farce.” Beyond these two extremes, MacLeish suggested, was an image of the planet as a kind of lifeboat, “that tiny raft in the enormous, empty night.”

Commander Borman himself compared Earth to an “aggie,” no doubt recalling playing marbles as a boy, drawing circles in the dirt. The famous “Blue Marble” image — one of the most reproduced photographs in human history — came four years later, from Apollo 17. But for Commander Borman and MacLeish alike, what “Earthrise” revealed wasn’t a marble made vast but a planet made small. A little blue sphere, a child’s precious aggie, floating alone in the abyss.

Much later, Carl Sagan would pick up this line of thought in his 1994 book, “Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space,” in which the Earth, as photographed in 1990 from the Voyager 1 from 3.7 billion miles away, became “a mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam.” For Sagan, this new image challenged “the delusion that we have some privileged position in the universe,” and at the same time “underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly and compassionately with one another and to preserve and cherish that pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

Since then, we’ve learned a great deal more. When Voyager 1 took that picture, we weren’t yet sure whether there were any planets at all outside our solar system. But today, largely thanks to space telescopes peering out from Earth’s orbit, we know we look up at night into a galaxy with more planets than stars. We may now perceive, as never before, the Earth’s exquisite rarity and value. We live on a marvel to behold.

We also know how our own DNA links us to one another and to life on our planet in general. We need not imagine ourselves as brothers and sisters, because science tells us that we are one family of life that includes plants, animals, birds, insects, fungi, even bacteria. All of life rides on Earth together.

By the time Sagan delivered his message “to preserve and cherish” our planet, the awareness of our responsibility to care for the Earth had already taken hold. In 2018, it is virtually impossible to see “Earthrise” without thinking of the ways the planet’s biosphere — proportionally as thin as a coat of paint on a classroom globe — is not only fragile but also under sustained attack by human actions. It is hard not to conclude that we have utterly failed to uphold the grave responsibility that the Apollo 8 crew and “Earthrise” delivered to us.

Our precious “raft” is losing members — species are dying — as our climate changes and our planet warms. The very technologies that flung us around the moon and back, the dazzling industrial genius that gave us fossil-fuel-fed transport and electricity, animal agriculture and all the rest, have fundamentally changed our Earth, and they now threaten to cook us into catastrophe. We may be afloat in MacLeish’s “eternal cold,” but what MacLeish couldn’t yet see was how, even then, we were madly stoking the furnace.

It’s all there in “Earthrise,” if we look closely enough. Those spiraling ribbons of clouds foreshadow the extreme weather to come. In the foreground, the gray moon testifies to how unforgiving the laws of nature can be. And behind the camera, so to speak, is the sprawling apparatus of the modern industrial age, spewing an insulating layer of haze around that little blue marble, the only home we’ve ever known.

Today, against the backdrop of our enormous challenge in salvaging the Earth, MacLeish’s message almost seems quaint, if not dated. (He wrote of brothers, no sisters mentioned.) And yet, the poet still has a point. The vision of “Earthrise” is still one of awe and wonder. As we continue to venture out beyond Earth’s orbit, we citizens of Earth can at least hope that we will still be humbled by each new vision of our lonely planet from space.

In the end, “Earthrise” is an icon of hope, not despair. That Christmas Eve 50 years ago, Commander Borman and his crewmates turned to another kind of poetry, some of the oldest on Earth. Broadcasting live from lunar orbit to what was then the largest television audience in history, the astronauts read the opening verses of the Book of Genesis, ending with verse 10: “And God called the dry land Earth. … And God saw that it was good.”

“And from the crew of Apollo 8,” said Commander Borman, signing off as the ship slipped around to the dark side of moon and out of broadcast contact, “good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas — and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.” In the silence of the moon’s dark side, they later recalled, the skies appeared brighter and deeper — all except for the ink-black disc of the lifeless moon itself, blocking out the stars.

By Matthew Myer Boulton and Joseph Heithaus

Mr. Boulton is a writer and a filmmaker. Mr. Heithaus is a poet.

Dec. 24, 2018

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

Climate Negotiators Reach an Overtime Deal to Keep Paris Pact Alive

Michal Kurtyka, president of the climate talks in Katowice, Poland, leapt over his desk as the final session ended... (continues)==

2018: The Year in Climate Change

From dire climate reports to ravenous urchins and vanishing heritage sites, here are the climate stories you shouldn’t miss from this year.Monday, December 17, 2018

Would Human Extinction Be a Tragedy?

Our species possesses inherent value, but we are devastating the earth and causing unimaginable animal suffering.

...Human beings are destroying large parts of the inhabitable earth and causing unimaginable suffering to many of the animals that inhabit it. This is happening through at least three means. First, human contribution to climate change is devastating ecosystems, as the recent article on Yellowstone Park in The Times exemplifies. Second, increasing human population is encroaching on ecosystems that would otherwise be intact. Third, factory farming fosters the creation of millions upon millions of animals for whom it offers nothing but suffering and misery before slaughtering them in often barbaric ways. There is no reason to think that those practices are going to diminish any time soon. Quite the opposite.

Humanity, then, is the source of devastation of the lives of conscious animals on a scale that is difficult to comprehend.

To be sure, nature itself is hardly a Valhalla of peace and harmony. Animals kill other animals regularly, often in ways that we (although not they) would consider cruel. But there is no other creature in nature whose predatory behavior is remotely as deep or as widespread as the behavior we display toward what the philosopher Christine Korsgaard aptly calls “our fellow creatures” in a sensitive book of the same name.

If this were all to the story there would be no tragedy. The elimination of the human species would be a good thing, full stop. But there is more to the story. Human beings bring things to the planet that other animals cannot. For example, we bring an advanced level of reason that can experience wonder at the world in a way that is foreign to most if not all other animals. We create art of various kinds: literature, music and painting among them. We engage in sciences that seek to understand the universe and our place in it. Were our species to go extinct, all of that would be lost.

Now there might be those on the more jaded side who would argue that if we went extinct there would be no loss, because there would be no one for whom it would be a loss not to have access to those things. I think this objection misunderstands our relation to these practices. We appreciate and often participate in such practices because we believe they are good to be involved in, because we find them to be worthwhile. It is the goodness of the practices and the experiences that draw us. Therefore, it would be a loss to the world if those practices and experiences ceased to exist... (continues)

...Human beings are destroying large parts of the inhabitable earth and causing unimaginable suffering to many of the animals that inhabit it. This is happening through at least three means. First, human contribution to climate change is devastating ecosystems, as the recent article on Yellowstone Park in The Times exemplifies. Second, increasing human population is encroaching on ecosystems that would otherwise be intact. Third, factory farming fosters the creation of millions upon millions of animals for whom it offers nothing but suffering and misery before slaughtering them in often barbaric ways. There is no reason to think that those practices are going to diminish any time soon. Quite the opposite.

Humanity, then, is the source of devastation of the lives of conscious animals on a scale that is difficult to comprehend.

To be sure, nature itself is hardly a Valhalla of peace and harmony. Animals kill other animals regularly, often in ways that we (although not they) would consider cruel. But there is no other creature in nature whose predatory behavior is remotely as deep or as widespread as the behavior we display toward what the philosopher Christine Korsgaard aptly calls “our fellow creatures” in a sensitive book of the same name.

If this were all to the story there would be no tragedy. The elimination of the human species would be a good thing, full stop. But there is more to the story. Human beings bring things to the planet that other animals cannot. For example, we bring an advanced level of reason that can experience wonder at the world in a way that is foreign to most if not all other animals. We create art of various kinds: literature, music and painting among them. We engage in sciences that seek to understand the universe and our place in it. Were our species to go extinct, all of that would be lost.

Now there might be those on the more jaded side who would argue that if we went extinct there would be no loss, because there would be no one for whom it would be a loss not to have access to those things. I think this objection misunderstands our relation to these practices. We appreciate and often participate in such practices because we believe they are good to be involved in, because we find them to be worthwhile. It is the goodness of the practices and the experiences that draw us. Therefore, it would be a loss to the world if those practices and experiences ceased to exist... (continues)

==

Todd May, professor of philosophy at Clemson University and the author of, most recently, “A Fragile Life: Accepting Our Vulnerability.” He is a philosophical adviser for the television show, “The Good Place.” (https://twitter.com/nbcthegoodplace)

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

5 books on the politics of climate change

| Five Books (@five_books) |

|

"You believe that if you get the factual information clear, explain it well, and make it available, then people will respond in a rational way. For scientists to discover that that’s not true has been quite a shocking state of affairs." (@NaomiOreskes)

fivebooks.com/best-books/pol… | |

‘We’re on a path that is going to lead to tremendous destruction and yet most of us are going about our lives as if nothing particularly special is happening.’ The science of climate change is incontrovertible but deniers persist and political and economic solutions continue to be – systematically – frustrated. Time is running out, says Naomi Oreskes.

The risks of climate change are increasingly clear and urgent. And yet, in the United States and some other countries, policies to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions do not seem to be working. The US President has called climate change a hoax and pulled the United States out of the Paris Agreement. And about 6.5 percent of global GDP — about 5 trillion dollars a year — goes to subsidising fossil fuels. How did we get into this situation in the first place?

Scientists have known for a long time that an increase in atmospheric greenhouse gases—produced by burning fossil fuel—could change the climate. By the late 1970s, it was clear that greenhouse gases were accumulating in the atmosphere, and scientists concluded that this would cause effects, probably by the end of the century. However, the observable effects came sooner than they expected: in 1988, scientists at NASA led by James Hansen, concluded that anthropogenic climate change was underway.

Hansen’s work got a good deal of attention. He testified in Congress. It was reported in the New York Times. And that same year the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was created, in anticipation that the world would need good scientific information to inform policy decisions on the issue. Most scientists involved at the time thought that there would soon be a political response. And there was, but it was not the one they expected.

Until that time, there was no political resistance to climate science. Many climate scientists were Republicans, and throughout most of the post-war period, Republican political and business leaders had supported scientific research as strongly, if not more strongly, than Democratic leaders did. But, in the 1980s—just as the reality of climate change was being established scientifically—some people began to realise that if anthropogenic climate change was as dangerous as scientists thought, it would require government action to deal with it. In particular it would require government intervention in the marketplace, such as regulation or taxation to reduce or even eliminate the use of fossil fuels... (continues)

==

==

| Nat Geo Channel (@NatGeoChannel) |

|

Paris to Pittsburgh celebrates the Americans developing solutions to curb climate change pic.twitter.com/QH8DAneGSG

| |

Andrew Revkin Retweeted

"Carl Sagan said extinction is the rule, survival is the exception and I think we are an exceptional species but we need to work at it," said @KenCaldeira closing The Sagan Lecture at #AGU18.

Monday, December 10, 2018

The Windup Girl: Final Blog Post

The Windup Girl Final Blog Post

Quiz:

1.) How does Anderson's story end? (He dies of the plague that originated in his own factory)

2.) What happens to the city? (Kenya blows up the wall as an act of rebellion and the city floods)

3.) Who helps Emiko achieve her dream? (Dr. Gibbons makes her able to reproduce and be with her own kind)

4.) What does Hock Seng hope to steal from Anderson? (The blue prints for the Kink Spring [fails])

Discussion Question:

Do you think that there are serious moral implications to Gibbons giving the New People the ability to reproduce?

•Not human/ more advanced (fearful)

Quiz:

1.) How does Anderson's story end? (He dies of the plague that originated in his own factory)

2.) What happens to the city? (Kenya blows up the wall as an act of rebellion and the city floods)

3.) Who helps Emiko achieve her dream? (Dr. Gibbons makes her able to reproduce and be with her own kind)

4.) What does Hock Seng hope to steal from Anderson? (The blue prints for the Kink Spring [fails])

Discussion Question:

Do you think that there are serious moral implications to Gibbons giving the New People the ability to reproduce?

•Not human/ more advanced (fearful)

Do you think that the world would fall into this state of anarchy and separatism if the world flooded?

Comments/ Midterm Report:

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/10/the-windup-girl.html

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/12/interstellar-final-blog-post.html?showComment=1544506826309#c8954473014246871829

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/12/the-collapse-of-western-civilization.html?showComment=1544507146481#c132422607422524630

Comments/ Midterm Report:

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/10/the-windup-girl.html

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/12/interstellar-final-blog-post.html?showComment=1544506826309#c8954473014246871829

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/12/the-collapse-of-western-civilization.html?showComment=1544507146481#c132422607422524630

The Drowned World by JG Ballard

In the second half of The Drowned World we follow Kerans, Beatrice, and Dr. Bodkins through what is left of London. The other biologists have abandoned the London station and headed north. The three have been so obsessed with their dreams that they rarely see each other. After six weeks of being on the their own Kerans spots a group of looters moving into town. They are led by an albino man who refers to himself as strangeman and are followed by two thousand alligator watch-dogs. Strangeman eventually finds the group and learns that Dr. Bodkins has knowledge of the city. He hopes to get Bodkins’ help in looting the city but is angered when Bodkins refuses. In an attempt to make looting easier on himself, Strangeman has his men dam and drain the entire city. This does not settle well with Dr. Bodkins who through his dreams has developed a strong connection to the lagoons. Out of desperation and in an unclear state of mind, Dr. Bodkins tries to plant a bomb in the dam. Before he can get away and set the bomb off, strangeman tosses the bomb into the lagoon, ruining his plan. Strangeman chases after Bodkins with a gun and we do not hear of him again.

After this incident, Strangeman, wanting no more surprises, captures both Kerans and Beatrice. Kerans is taken into the streets and tortured nearly to death while Beatrice is held in Strangeman’s home. Kerans awakes in the streets, tied to a chair. He realizes the chair arms are broken and is able to wiggle his way out. Knowing Strangeman has Beatrice, he starts planning to rescue her. With only a broken compass and a small gun Kerans makes his way to strangeman’s hideout. He is able to get in and find Beatrice, but they are not able to get out without being seen. Strangeman chases the couple and corners them in the street. Here Strangeman offers to spare Beatrice if Kerans will turn himself over. Kerans refuses and it seems this may be the end for the couple. At the last moment, the group sees a helicopter preparing to land and a familiar face inside.

At the sight of the military helicopter Strangeman and his crew fled. Colonel Riggs informs the couple that he heard Strangeman was in the area and knew they would be in for trouble. Though the two still do not wish to put their dreams aside, Riggs insists he will be taking them north with him. The next morning as the group is preparing to leave, a massive solar system hits. This destroys the helicopter and killss both Beatrice and Colonel Riggs. Kerans is blown and knocked unconscious. He awakes to a familiar voice. He realizes this is Dr. Hardman though he looks much different. In the following days Kerans attempts to care for Hardman, but he does not recognize Kerans. Eventually kerans wakes to realize Hardman is gone. Kerans waits for him for a few days, but he never returns. Kerans decides to continue south, giving in to his dreams and ultimately accepted his death.

*************************************************************************************

The Drowned World paints a very vivid picture of a dystopian world that holds the potential to one day become a reality. Different from other novels used in the course, The Drowned World displays a world of environmental disaster that is not due to human impacts. Instead, this downfall was due solely to solar instability. I do not believe Ballard intended an environmental message when this book was published in 1962. I believe he wrote this novel simply to entertain an audience interested in dystopian societies, though I do think we can find meaning in it in today’s world. This novel opens the question “Could natural disasters end our world as we know it?” Obviously, the answer is yes, they could. But this opens the door to a series of more questions. Will a natural disaster destroy the environment before humans? Do we have the technology to predict such disasters? Is there anything we could do to slow the impacts of such a disaster? Though I do not think Ballard meant to give this novel an environmental message, I do believe it was very good one to study for this class. It forces you to think about our constantly changing environment and how quickly it can be flipped upside down, as well as how a changing environment can affect the human population. The Drowned World paints a vivid picture of a dystopian future that could become the present in the blink of an eye.

Comments

Elon Musk on 60 Minutes

...GM also announced that it will double its investment into developing electric cars, and Elon Musk is celebrating.

Lesley Stahl: Why do you want the competition?

Elon Musk: The whole point of Tesla is to accelerate the advent of electric vehicles. And sustainable transport and trying to help the environment. We think it's the most serious problem that humanity faces. I'm not sure if you know it, but we open sourced our patents, so anyone who wants to use our patents can use 'em for free.

Lesley Stahl: Your patents are open-sourced?

Elon Musk: Yeah. If somebody comes and makes a better electric car than Tesla and it's so much better than ours that we can't sell our cars, and we go bankrupt, I still think that's a good thing for the world.

Lesley Stahl: And you'll sleep at night.

Elon Musk: Yeah, because somebody's making some pretty great cars. Um, yeah.

60 Minutes, Dec.9, 2018

Green New Deal-Call Now

Just received this text message from 350.org:

RIGHT NOW, 1000+ young people are in DC to demand Congress support a #GreenNewDeal. Call your Rep NOW to make sure they get the message: bit.ly/supportGND

Sunday, December 9, 2018

Odds Against Tomorrow Part Two:

Nathaniel Rich’s Odds Against Tomorrow leaves readers with an unexpected urgency to prepare for the worst. The novel dives into the probability and statistics of natural disasters occurring, slowly drawing the audience into believing that anything can happen at any moment. The journey we take with Mitchell throughout his everyday life and eventually through the chaos Mother Nature brings to Manhattan, provides us with a quirky protagonist that learns to value a humble lifestyle.

In the latter half of the book, New York begins suffering a major drought. This results in FutureWorld becoming very busy with clients. The founder, Alec Charnoble, hires a new consultant to help Mitchell balance the new surge of clients. Jane is pretty and a great saleswoman. She quickly learns how to do her job efficiently and helps Mitchell construct drought scenario pitches for clients. The pair worked diligently until a rain cloud appears one afternoon. The drought finally ends and the rain begins to pour, causing Jane to drag Mitchell outside to celebrate. While in the nearby park, Mitchell notices how quickly the ground is forming puddles. He concludes that the ground has turned to tightly compacted dust that will not soak up the rain.

After the pair return, Mitchell suggests they begin crafting flood scenarios although, Jane and Alec laugh this off. Later that night, it is announced that tropical storm Tammy is headed straight for New York, causing Mitchell to panic. Tammy is soon upgraded to a category 2 hurricane with the potential to become a category 4 by landfall. Alec then allows Jane and Mitchell to pitch flood scenarios to clients.

The Hurricane hits soon after word, flooding New York just has Mitchell predicted. Him and Jane take cover in his third floor apartment. The storm made it to a category 3, but had a major impact on the city of Manhattan. After the storm, Jane and Mitchell search for rescue and eventually find a FEMA station. Their stay is short lived however. Mitchell is soon attacked for being a ‘prophet’ and not warning the public about this disaster. He soon finds out that Charnoble has been name dropping in interviews, revealing that Mitchell knew from the first rain drop what was in store for the state. They couple leave the camp the falling the day in hopes of reaching the Flatlands. Mitchell theorizes that this area would be less flooded than surrounding areas.

Three days later they make it to the Flatlands. They quickly make home in a second story bank lobby and break into the local grocery store for food and supplies. They make camp there for several days until Jane has had enough. She leaves Mitchell behind to find another rescue camp. Mitchell begins to enjoy this version of life. He picks up farming and become one with nature. About a week later a couple comes by to look for him. They have a message from Jane, stating that she has made it back to Manhattan, which was reopened three days prior. They explain how the state Government divided the decimated areas into 5 specific zones. Each would be restored in numerical order, except for zone five which incorporates the Flatlands. This area will remain a wetlands area and will not go under any reconstruction. Oddly, this delights Mitchell and he decides to remain in the Flatlands, to re closer with nature. This completely contradicts his character at the beginning of the story, desperate to move to New York and live comfortably in the big city.

The story wraps up with Jane visiting Mitchell on a monthly basis, making sure he still has everything he needs. She reveals that she began her own disaster consultant business and they are thriving just as FutureWorld did. She tries to convince him to come with her, but he refuses. Nature is his true home, and he will never leave it again.

Midterm:

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/10/odds-against-tomorrow.html

Comments:

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/12/ecotopia-final-report.html?showComment=1544496121522#c5712273520002841286

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/12/the-wastelanders-final-report.html?showComment=1544496671598#c1951750847019700185

In the latter half of the book, New York begins suffering a major drought. This results in FutureWorld becoming very busy with clients. The founder, Alec Charnoble, hires a new consultant to help Mitchell balance the new surge of clients. Jane is pretty and a great saleswoman. She quickly learns how to do her job efficiently and helps Mitchell construct drought scenario pitches for clients. The pair worked diligently until a rain cloud appears one afternoon. The drought finally ends and the rain begins to pour, causing Jane to drag Mitchell outside to celebrate. While in the nearby park, Mitchell notices how quickly the ground is forming puddles. He concludes that the ground has turned to tightly compacted dust that will not soak up the rain.

After the pair return, Mitchell suggests they begin crafting flood scenarios although, Jane and Alec laugh this off. Later that night, it is announced that tropical storm Tammy is headed straight for New York, causing Mitchell to panic. Tammy is soon upgraded to a category 2 hurricane with the potential to become a category 4 by landfall. Alec then allows Jane and Mitchell to pitch flood scenarios to clients.

The Hurricane hits soon after word, flooding New York just has Mitchell predicted. Him and Jane take cover in his third floor apartment. The storm made it to a category 3, but had a major impact on the city of Manhattan. After the storm, Jane and Mitchell search for rescue and eventually find a FEMA station. Their stay is short lived however. Mitchell is soon attacked for being a ‘prophet’ and not warning the public about this disaster. He soon finds out that Charnoble has been name dropping in interviews, revealing that Mitchell knew from the first rain drop what was in store for the state. They couple leave the camp the falling the day in hopes of reaching the Flatlands. Mitchell theorizes that this area would be less flooded than surrounding areas.

Three days later they make it to the Flatlands. They quickly make home in a second story bank lobby and break into the local grocery store for food and supplies. They make camp there for several days until Jane has had enough. She leaves Mitchell behind to find another rescue camp. Mitchell begins to enjoy this version of life. He picks up farming and become one with nature. About a week later a couple comes by to look for him. They have a message from Jane, stating that she has made it back to Manhattan, which was reopened three days prior. They explain how the state Government divided the decimated areas into 5 specific zones. Each would be restored in numerical order, except for zone five which incorporates the Flatlands. This area will remain a wetlands area and will not go under any reconstruction. Oddly, this delights Mitchell and he decides to remain in the Flatlands, to re closer with nature. This completely contradicts his character at the beginning of the story, desperate to move to New York and live comfortably in the big city.

The story wraps up with Jane visiting Mitchell on a monthly basis, making sure he still has everything he needs. She reveals that she began her own disaster consultant business and they are thriving just as FutureWorld did. She tries to convince him to come with her, but he refuses. Nature is his true home, and he will never leave it again.

Midterm:

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/10/odds-against-tomorrow.html

Comments:

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/12/ecotopia-final-report.html?showComment=1544496121522#c5712273520002841286

https://envirojpo.blogspot.com/2018/12/the-wastelanders-final-report.html?showComment=1544496671598#c1951750847019700185

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)