In the chapter titled

"Will the Future Be Good or Bad?", William MacAskill grapples with

the complex question of whether the average human life is better than nothing.

This philosophical dilemma involves weighing the benefits and burdens of

existence. One section that piqued my interest was titled “Nonhuman Animals,”

which, as a phrase, stood out to me because it utilizes the categories “human” and

“nonhuman.” While I understand that humans are technically classified as

animals, the distinction between “human” and “nonhuman” is not often emphasized

when we talk about animals. This made me think about the broader implications

of the relationship between humans and “animals,” both in terms of how we treat

them and the impact we have on their lives.

MacAskill argues that

when assessing whether the world is good or bad, it is necessary to consider

more than just human experience. There are other sentient beings on

Earth—nonhuman animals—that are also affected by anthropogenic forces and, most

notably, climate change. But perhaps more significantly, the author points out

the role that humans play in shaping the lives of animals, focusing on the

negative ways we impact them. This led me to reflect on how we, as a species,

interact with the planet’s nonhuman inhabitants, especially the animals that we

farm for food.

As someone who grew up in

a rural area surrounded by farms, particularly livestock farms, I have seen

firsthand how animals are raised for food production. I even raised my own

animals at one point, which added an additional layer to how I viewed the

treatment of animals in the food industry. In this chapter, MacAskill

highlights the staggering numbers of animals killed annually for food.

According to the data, “over 79 billion vertebrate land animals were killed in

2018 alone, including 69 billion adult chickens, 3 billion baby male chicks, 3

billion ducks, and other species such as pigs, quail, sheep, and cattle. In

addition, around 100 billion fish are slaughtered in fish farms every year” (208).

Production of animal products has increased significantly. The

sheer scale of this is jarring, and it forces us to confront the ethical

implications of factory farming.

The passage goes on to

describe the physical and emotional suffering that these farmed animals endure daily.

For instance, broiler chickens, also known as the type raised for meat, and

egg-laying chickens are subjected to harsh conditions from birth to slaughter.

Many of these animals undergo painful mutilations, such as cutting off beaks

and castrating males without anesthesia. The chickens are often kept in

overcrowded, unsanitary conditions, where diseases rapidly spread. Although

they may experience somewhat less suffering compared to chickens, cattle and

pigs still endure significant harm in their lives, such as close confinement

and rough handling. The pain and suffering of fish in industrial fish farms is

also highlighted by MacAskill. Fish are confined to overcrowded pens, where

they are at risk of injury, disease, and premature death due to the stress and

physical constraints of their environment. Animal Law has a list of pending

legislation that relates to the abuse of animals in

CAFOs.

After reading this

section, I decided to investigate the practices of factory farms further.

Factory farms, also known as Concentrated

Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), are large-scale industrial

facilities where animals are raised for profit under inhumane conditions. These

farms typically house thousands of animals in confined spaces, where they are

fed antibiotics and growth hormones to maximize their production. CAFOs are spread

widely across the United States.

An article by Animal Equality, an organization focused on animal rights, discusses some of the most cruel yet legal farming practices common in CAFOs. These practices are shocking in their disregard for the well-being of the animals involved. One such practice is the routine use of painful procedures such as tail docking in pigs, removal of chicken beaks, and the confinement of cows in narrow stalls that prevent them from turning around at all. Another particularly egregious practice is the use of “battery cages” for egg-laying hens, where the birds are confined to tiny spaces, unable to move freely or engage in natural behaviors. This close confinement has led to cannibalism amongst the groups of chickens. These practices are not only cruel but also serve as stark examples of how profit-driven industries prioritize saving and making money over the welfare of the animals.

As

I continued to explore the consequences of factory farming, it became clear

that the impact extends far beyond the animals themselves. The environmental

toll of CAFOs is staggering, with significant damage done to both the water and

air quality in areas where these farms are concentrated. CAFOs produce vast

amounts of animal waste, much of which ends up contaminating local water

supplies. States that dominate the CAFO industry experience on average 20 to 30

serious water quality issues every year, affecting both surface water and

groundwater. This pollution, which includes harmful chemicals and pathogens, leads

to serious health problems for the local population. One of these health issues

is the spread of waterborne diseases. In addition, the waste produced by CAFOs

contributes to air pollution, as gases such as ammonia and methane are released

into the atmosphere. These gases are not only harmful to human health but also

contribute to climate change by trapping heat in the atmosphere.

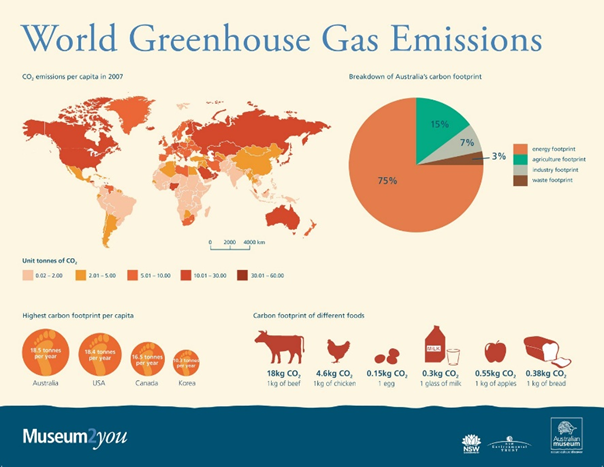

Image 2:

Carbon Footprint. Take note of the bottom right section

Beyond the environmental

effects, CAFOs also have a profound economic impact. As the scale of these

operations has grown, small-scale family farms have been pushed out of the

market. The low-cost, high-efficiency model of CAFOs allows them to produce meat,

eggs, and milk at a fraction of the cost of more humane alternatives, such as

free-range or organic farms. This economic advantage has led to the dominance

of industrial farms, which produce most animal

products consumed in the United States. As a result, smaller, more

sustainable farms that prioritize animal welfare and environmental health

struggle to compete. The negative ecological effects of CAFOs, such as water

and air pollution, are not reflected in the price of the meat and other products

they produce, meaning that the true costs are borne by society rather than by

the farms themselves.

I posed this question in class: "Are we breeding these animals into stupidity?" I believe they are. What is the next evolutionary standpoint for these animals? To live purely to be slaughtered? If we keep breeding these animals in the conditions that we are, they will literally just be food. We have domesticated these animals to the point that seeing them "in the wild" is borderline impossible. They have no life outside of breeding and slaughter. I posed another question: "How would we feel in their situation?" Sure, we are viewed as a more intelligent species, but these animals feel pain too. How can we ethically treat them this way? We wouldn't want to be treated this way.

In conclusion, the

treatment of nonhuman animals, particularly in the context of factory farming,

raises profound ethical, environmental, and economic questions. MacAskill’s

chapter encourages us to expand our view of the world and consider the impact

of our actions on all sentient beings, not just humans. The suffering of farmed

animals, along with the damage caused by CAFOs to the environment and local

communities, underscores the urgent need for change in how we produce and

consume animal products. Whether through more humane farming practices, shifts

in consumer behavior, or changes in legislation, we must take responsibility

for the way we treat the animals with whom we share the planet.

I just got my PETA packet in the mail. This might be my tipping point...

ReplyDelete