Stewart Brand, Clock of the Long Now: Time and Responsibility: The Ideas Behind the World's Slowest Computer

Using the designing and building of the Clock of the Long Now as a framework, this is a book about the practical use of long time perspective: how to get it, how to use it, how to keep it in and out of sight. Here are the central questions it inspires: How do we make long-term thinking automatic and common instead of difficult and rare? Discipline in thought allows freedom. One needs the space and reliability to predict continuity to have the confidence not to be afraid of revolutions Taking the time to think of the future is more essential now than ever, as culture accelerates beyond its ability to be measured. Probable things are vastly outnumbered by countless near-impossible eventualities. Reality is statistically forced to be extraordinary; fiction is not allowed this freedom. This is a potent book that combines the chronicling of fantastic technology with equally visionary philosophical inquiry. g'r

- Is the clock project cuckoo?

- Does the clock project strike you as comparable, in conception and intention, to Brand's late-60s rooftop epiphany about the importance of an image of the "whole earth"? (see * below)

* He came up with the idea of a photo of the entire Earth from space "thanks to an LSD experience on a rooftop in San Francisco." At least that's how Stewart Brand — author and founder of boundary-pushing organizations — describes it.

During his trip, "I got thinking about something that [Buckminster] Fuller talked about, that a lot of people assume that the Earth is flat and kind of infinite in terms of its resources, but once you really grasp that it's a sphere and that there's only so much of it, then you start husbanding your resources and thinking about it as a finite system," says Brand in the TED interview with Chris Anderson in the video below. So in 1966, Brand campaigned NASA to take such an image. He even printed and distributed buttons printed with the query: "Why haven't we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?"

Stewart Brand's Whole Earth Catalog, the book that changed the world

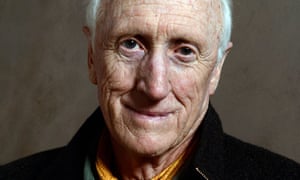

Stewart Brand was at the heart of 60s counterculture and is now widely revered as the tech visionary whose book anticipated the web. We meet the man for whom big ideas are a way of life

Stewart Brand didn't just happen to be around when the personal computer came into being; he's the one who put "personal" and "computer" together in the same sentence and introduced the concept to the world. He wasn't just a member of the world's first open online community, the Well; he co-founded it. And he wasn't just another of those 60s acid casualties; he was the definitive 60s acid casualty. Well, not casualty exactly, but he was there taking LSD in the days when it was still legal, with the most famous hipster of them all, Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters.

For nearly five decades, Stewart Brand has been hanging around the cutting edge of whatever is the most cutting thing of the day. Largely because he's discovered it and become fascinated with it long before anyone else has even noticed it but, in retrospect, it does make him seem like the west coast's answer to Zelig, the Woody Allen character who just happens to pop up at key moments in history. Because no one pops up like Stewart Brand pops up, right there, just on the cusp of something momentous.

I discover this for myself when I go and hunt down my ancient copy of Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. It's one of the defining pieces of new journalism, a rip-roaring ride through 1960s psychedelia in which Wolfe accompanies Kesey and the Pranksters across the States on a Day-Glo bus. And although I know about Brand's connection to Kesey, I didn't know he was in it. But of course he is, right there on page two, driving the Pranksters' pick-up truck ("a thin, blond guy", according to Wolfe, with "a blazing disk on his forehead" and "a whole necktie of Indian beads … but no shirt").

"That is classic Stewart," says Fred Turner, associate professor of communication at Stanford, who has written a book about Brand. "He only hung out with the Pranksters for about 10 minutes."

And he's right there on page two, of the definitive account of them.

"Exactly. He has a sort of genius for being in exactly the right place at exactly the right time."

It is a sort of genius. The same year that Tom Wolfe's book came out – 1968 – Brand just happened to be at what came to be known as the "mother of all demos" when the world first saw what computers could do. Douglas Englebart astonished the 1,000 foremost computer scientists with the first computer mouse, the first teleconferencing, the first word processing, and the first interactive computing. (Being Stewart Brand, of course, he wasn't just there, he was operating the camera and consulting on the presentation.)

What's more, later that same year he published the first edition of what came to be the magnum opus of the entire counterculture, the Whole Earth Catalog – a book that some people, Turner included, believed changed the world. Though it wasn't exactly a book, it was a how-to manual, a compendium, an enyclopedia, a literary review, an opinionated life guide, and a collection of readers' recommendations and reviews of everything from computational physics to goat husbandry.

This year marks its 45th anniversary. I have a slightly later, yellowing and decrepit edition, from 1971, though it's the same oversized format. It's the edition that sold 2m copies and won a US National Book award, and the tips on spot welding, home remedies for crabs (not the marine kind, I don't think), dealing with drug busts, and building your own geodesic dome are rather delightfully quaint. (I especially like an extract from the underground guide to US colleges which states that, at the University of Illinois: "The hip chicks will do it. It is easier to find a chick who will have sex now than it was two years ago when things were extremely difficult.") But it doesn't even begin to convey the revolution that the Whole Earth Catalog represented.

But then, it's almost impossible, to flick through the pages of the Catalog and recapture its newness and radicalism and potentialities. Not least because the very idea of a book changing the world is just so old-fashioned. Books don't change anything these days. If you want to start a revolution, you'd do it on Facebook. And so many of the ideas that first reached a mainstream audience in the Catalog – organic farming, solar power, recycling, wind power, desktop publishing, mountain bikes, midwife-assisted birth, female masturbation, computers, electronic synthesizers – are now simply part of our world, that the ones that didn't go mainstream (communes being a prime example) rather stand out.

Turner's 2006 book, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network and the Rise of Digital Utopianism, gives more of a clue. Several epoch-making events were going on in the San Francisco area in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, and at the centre of them all, linking them together – no surprises here – was Stewart Brand.

Ken Kesey believed that drugs would herald a new era of human consciousness. While scientists like Doug Englebart (who had, like Brand, taken part in LSD-assisted creativity sessions) came to believe that computers would be part of that. They were were developing the hardware while Brand was articulating a vision of how they might be a new tool to empower ordinary people: small scale, democratic and free.

Or, as John Markoff, a technology writer for the New York Times, puts it, the Whole Earth Catalog was "the internet before the internet. It was the book of the future. It was a web in newsprint."

It changed the world, says Turner, in much the same way that Google changed the world: it made people visible to each other. And while the computer industry was building systems to link communities of scientists, the Catalog was a "vernacular technology" that was doing the same thing.

"And Stewart knew this because he's sitting here in the middle of the tech world. But much of the rest of America can't see that yet. But he can see it. And he makes it visible and he makes it cool – and these things are important."

Forty-five years on and he's still cool. Mick Jagger might be the most obvious 60s icon who's kept on rocking. But mostly he's kept on rocking all the old tunes. Stewart Brand, on the other hand, has continued to evolve and change and at the age of 74, he's still out there at the intellectual cutting edge.

The Whole Earth Catalog may have been his most famous creation, but he's been involved in dozens of other, possibly even more influential, projects since. I interview him at the TED conference in Long Beach where he'd just delivered a talk (his fifth at TED) on his latest enthusiasm, which is about as radical as they come: de-extinction. He's trying to resurrect extinct species by retro-engineering their DNA.

In many ways, he's the elder statesman of radical ideas, an emissary from the Sixties counterculture who continues to inspire each successive generation anew; a living link between the heady days of the pioneering new technology and today.

John Markoff, who wrote What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry, says, simply: "Stewart was the first one to get it. He was the first person to understand cyberspace. He was the one who coined the term personal computer. And he influenced an entire generation, including an entire generation of technologists."

It is in no way hard to find people who have been inspired by the Whole Earth Catalog and by Stewart Brand. Chris Anderson, curator of TED, the conference series for "ideas worth spreading", tells me that "in my own mind, he's my intellectual hero". Chris Anderson – yes, there's two of them – a former editor of Wired and leading light in the "maker movement" of industrial DIYers – describes him as "an international treasure" and "one of my gods". He actually thanks me for writing about him. Stewart Brand, it turns out, is the hero's hero.

And to no one more so than Steve Jobs. No one was more influenced, or inspired by, Stewart Brand, than the founder of Apple. And while many credit Jobs with being one of the most creative agents of change in the late 20th century, Jobs credited Brand.

Steve Jobs's Stanford commencement address, a short talk that he gave in 2005 and which went viral after his death in 2011, is, in many ways, the ne plus ultra of Jobsian wisdom. It encapsulated his thoughts on life, love and death. It expressed his lifelong philosophy and motivation. And it ends with a moving tribute to Brand and what he calls "an amazing publication called the Whole Earth Catalog", which he describes as "one of the bibles of my generation". It's worth quoting the rest of it in full: "It was created by a fellow named Stewart Brand not far from here in Menlo Park, and he brought it to life with his poetic touch. This was in the late 1960s, before personal computers and desktop publishing, so it was all made with typewriters, scissors, and Polaroid cameras. It was sort of like Google in paperback form, 35 years before Google came along: it was idealistic, and overflowing with neat tools and great notions.

"Stewart and his team put out several issues of the Whole Earth Catalog, and then when it had run its course, they put out a final issue. It was the mid-1970s, and I was your age. On the back cover of their final issue was a photograph of an early morning country road, the kind you might find yourself hitchhiking on if you were so adventurous. Beneath it were the words: 'Stay Hungry. Stay Foolish.' It was their farewell message as they signed off. Stay Hungry. Stay Foolish. And I have always wished that for myself. And now, as you graduate to begin anew, I wish that for you."

Were you surprised when you heard that, I ask Brand. "I was, yes, though I'd known it meant something to him as I'd been told that he wanted a copy of the cover of 'Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish' signed by me. And I signed one and sent it off to him. That was the first inkling I had that it mattered to him. But I wish I'd had a chance to really quiz him on what he got from that.

"I think he used it as a way to deal with the amount of wealth and power that was accumulating around him. That though he took great care to make sure that it did accumulate, it was a way to keep himself two-minded about it. I think it may have been the way of dealing with the innovator's dilemma, where to keep building on the new innovations you have to destroy the wonderful thing you built a couple of years ago.

"And remember this was the 70s. We were: fuck around with it, mess with it, try it sideways. That was what it was all about. I was an early hippy as it turned out, and Steve Jobs was a late hippy, and we were paying attention to the beatniks and the late hippies were paying attention to the early hippies and so it goes on."

Jobs may have given the world the Apple 2 and iTunes and the iPhone but he's the heir to a cultural mash-up that Brand was both an observer of and a participant in: hippies and computers. And for those puzzled by the confluence of Steve Jobs's professed peace'n'love ideals and his life spent making shiny consumer durables, Fred Turner points out that the Catalog was at its heart "deeply consumerist". I hadn't really thought of in that way but as Turner says "it's full of stuff to buy. All those down jackets and kayaks. It's one of the first places you see the earliest mountain bikes." It offers a vision of changing the world, he says, through buying stuff, an "idea which has stuck around".

There was nothing in Brand's background to suggest that he would become this pivotal figure. He was brought up in Rockford, Illinois, where his father worked in advertising and his mother was a Vassar-educated space fanatic, an enthusiasm that rubbed off on her son. He studied biology at Stanford and then had a stint in the army where he became a "weekend hippy and weekday soldier".

It was meeting the Beats that changed everything. He took up photography and started photographing Native American reservations around the country and it is was this link that led him to Ken Kesey, who had featured a Native American as a central character in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. "I got his address from a mutual friend and he said come on by. So I went on by and was met at the door by somebody with a joint. Next thing I knew I was part of the scene."

But his encounter with Kesey came at the same time as his encounter with another San Francisco phenomenon. "I was at the Stanford computation centre and this was some time in the early 60s and I saw these young men playing Spacewar! [an early computer game]. They were out of their bodies in this game that they'd created out of nothing. It was the only way to describe it. They were having an out-of-body experience and up until that time the only out-of-body experiences I'd seen were drugs."

It wasn't until 1972 that Brand wrote about it, and he still wrote about it before anyone else, in Rolling Stone magazine, an article that is so prophetic, it's almost hallucinatory. Brand's revelation, that he understood before almost anyone else, was that cyberspace was some sort of fourth dimension and the possibilities were both empowering and limitless.

At that time, computers weren't hip. They weren't cool. They were controlled by faceless corporations and the military. They were Big Business and authority, or, as they said then, "The Man". "What Buckminster Fuller was saying and what Marshall McLuhan was saying and what I was saying, all in our different ways, was that technology is liberating if you make it so. And a fair number of the hippies bought that programme. I guess Steve Jobs is the most conspicuous one. He was a total hippy, his last words were 'Oh wow' – he said it three times, according to his sister."

It was also the starting point for another of Brand's most famously repeated ideas: that information wants to be free (although he always points out the second half of the sentence was that "it also wants to be expensive").

"We are as gods and might as well get good at it," wrote Brand on the title page of the Whole Earth Catalog. Up until now, he noted, power has been in the hands of "government, big business, formal education, church". But now "a realm of intimate, personal power is developing – power of the individual to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment and share his adventure with whoever is interested. Tools that aid this process are sought and promoted by the Whole Earth Catalog."

In his mind, he says, he had "Diderot and his Encylopédie and this Enlightenment idea that basically knowledge had been held back by the aristocrats and all the rest. The whole thing was to keep people from knowing how to do things. So Diderot was in my mind. And so was the LL Bean catalogue which was full of outdoors stuff."

His hero was Buckminster Fuller, a futurist architect and designer, who he says "bent my twig" with what Brand calls a "psychedelic version of engineering".

"Fuller said if all the politicians died this week it would be a nuisance, but if all the scientists and engineers in the world died it would be catastrophic. So where's the real juice here?

"And he really got me and others focused on that. Lots of people try and change human nature but it's a real waste of time. You can't change human nature, but you can change tools, you can change techniques." And that way "you can change civilisation".

Kevin Kelly, the founding editor of Wired magazine, tells me how he first came across the Catalog when he was still in high school "and it changed my life. But then it changed everybody's life. It inspired me not to go to college but to go and try and live out my own life. It was like being given permission to invent your own life. That was what the Catalog did. It was called 'access to tools' and it gave you tools to create your own education, your own business, your own life."

Chris Anderson, the later editor of Wired, who is younger than both Brand and Kelly, says that he is absolutely the inheritor of the Catalog's "chain of influence". "The Whole Earth Catalog inspired the Homebrew Computing Club, who inspired Steve Wozniak to build the Apple 2, who inspired the personal computer movement, who in turn inspired the original web. Who inspired the open-source software movement. Who inspired the open-source hardware movement which inspired the maker movement who inspired me."

What's perhaps most remarkable about Brand, though, is the way that he himself has stayed hungry, has stayed foolish. Markoff says that his extraordinary capacity to be at the edge of the change "has puzzled me for years. Some people will be at the heart of one event but not over and over a long period of time. It can't be happenstance to keep on doing it."

He made millions from the Catalog but gave most of it away. At the final party he experimented with giving away $20,000 in cash because he thought that the extra stimulation of handing over wads of notes would "be an interesting thing to do. And indeed it was an interesting thing to do. I did not turn out any particularly creative ideas, I have to say. That was part of what made it interesting. My hypothesis was that under duress people would get extra creative. But it turns out they become extra knee-jerk and the opposite of creative. But you know, that's how you find out these things."

Turner calls him the most influential person you've never heard of, and though in Silicon Valley he's a god to many he still lives on a houseboat in Sausalito just outside San Francisco, and in the flesh is modest and unassuming. He looks like the fit and active 74-year-old he is, dressed in clothes that look like they'd take him straight from a conference hall to a hike in the mountains. I'd thought he might be quite forbidding but he's a great storyteller with a healthy sense of humour that he's happy to turn against himself.

Can he remember where the idea for "stay hungry, stay foolish" came from? "That one is a mystery," he says at first. And then, "Oh I know, it's because of my campaign to get photographs of the whole Earth which I did in 1966 and after which the Whole Earth Catalog is named.

"We were just starting to get files of photographs of the Earth, and there was a sequence from a satellite of basically a day in the life of Earth from sunrise to sunset, and I wanted that sequence and to make the connection between the view from space of the shadow moving across the Earth, and the experience of being on Earth and seeing dawn. And for some reason the image I had in my mind was of a hitchhiker at dawn on a road somewhere and the sun comes up and there are trains going by. The frame of mind of the young hitchhiker is one of the freest frames of mind there is. You're always a little bit hungry and you know you are being completely foolish."

It's a long explanation but what's interesting is how it ties in Brand's cosmic view of Earth, expanded consciousness (he first started his campaign to get photographs of the Earth from space after an LSD trip in which he thought he could see the curvature of the Earth), science – the Nasa space programme – and personal freedom.

He's always someone who's been able to take the long view, says TED's Chris Anderson. "I see him as someone whose life's work has been making people see the world in a different way."

In recent years, he established the Long Now Foundation, which aims to promote long-term thinking (projects include building a clock that will keep time for 10,000 years, ticking once a year and chiming to mark each millennium). He's written on architecture in How Buildings Learn, he's shaken up the ecology movement with Whole Earth Discipline – in which, among other things, he espouses mass urbanisation and nuclear power and then of course there's "de-extinction".

He's working alongside his wife, Ryan Phelan, a biotech entrepreneur, and George Church, the leading Harvard geneticist, and there's more than a touch of Jurassic Park to the concept. They're trying to retro-engineer lost species by comparing their DNA with that of their closest living relatives – though sadly they're starting with the American passenger pigeon rather than Tyrannosaurus rex.

Once the most populous bird in North America, its extinction was a "tragedy", Brand says in his TED talk, but then adds: "Don't mourn, organise."

This could be another of Brand's maxims. He's always been a doer. Kevin Kelly tells me that he says when he has an idea, he tries to act on it within 10 minutes, which just seems impossibly dynamic. But then, Fred Turner points out, "he's also had a lifetime of organising. And a lifetime teaches you things. I assure you that when he was much younger he did not feel he needed to get things done in 10 minutes. He would do things like take his entire production staff out into the desert, inflate a giant plastic bubble, and try to live around and inside that bubble to see how that affected production."

Adversely, it turned out. But then Brand is first and foremost a scientist. As was the case when he gave away $20,000 in cash, he wants to test things empirically. He's an experimenter who's always prepared to test his theories. ("It may have been the entire function of communes to go big, fail and then go home," says Brand, to take one example. "At the time we thought we were reinventing civilisation but all we discovered is that free love isn't free at all, that [when] one guy puts up all the money for your commune he is going to feel robbed after a period of six to 12 months, that gardening is actually hard, and that if you treat your women as people who are supposed to wash the dishes, they will leave after six months.")

The drugs didn't work. Or at least only for a bit. "We believed there was no hope without dope but we were wrong. I'm always amazed there aren't drugs by now, but there aren't. They didn't get any better, whereas computers never stopped getting better."

He didn't just theorise about cyberspace, he co-founded the Well, the pioneering online community in the 80s, and lived on it, fighting the first flame wars, the first trolls, making the first mistakes (he wishes he'd insisted the people used their real names rather than post anonymously, an innovation that may well have changed the web for the better).

And he's still out there on the leading edge today. It's no surprise that he's into biotech. It really is the next frontier, though he claims at the moment that he's not so much surfing the next wave of innovation as "paddling to keep up".

There used to be a sense, though perhaps less so now, that there would never be as exciting a time as the 60s again. And yet Brand, who had the best of the 60s, who really was there and can even remember it, is so much more excited by the present, by the future.

"It's much much more exciting right now. The tools of connectivity are so much stronger. The tools of empowerment have absolutely lowered the thresholds of entry. There's things like the iGem with tens of thousands of students producing new organisms. And society is not noticing. I find that both strange, wonderful and in some ways a little bit disturbing."

And it's possibly worth noticing what Stewart Brand is noticing. "Think about the Bay Area in the early 60s," Fred Turner tells me. "He could have focused on antiwar protests, on fluorescent parties, on any number of things. He goes to a basement in Stanford and watches people run a computer game."

Brand's career is as extraordinary and eclectic as they come. As they used to say in the 60s, it's been quite a ride. And yet I still hesitated over whether to include this last quote on him. It's rather delightfully of its time but it's also so over the top. Or is it? It's Kevin Kelly (whom Wired's Chris Anderson describes as "the patron saint of the technology movement") who says it to me. "I've had maybe a daily encounter with Stewart on email or whatever for at least 20 years, and every day I'm more impressed with him. He is genuinely… I don't know what the word is… an inspiring, uplifting, helpful force in the world. I've seen him in many situations, I've seen him under stress, I've seen him in private, and I have never been disappointed."

And then, a hippy – like Brand, like Jobs – to the last, Kelly adds: "If it was possible to be an enlightened person, I would say he's an enlightened person."

The publication gave rise to a new community of environmental thinkers, where hippies and technophiles found common ground... Smithsonian

On Monday we'll meet at 3, I'll be in a Zoom workshop 'til then.

We'll talk about whatever y'all want this week. I suggest we take another look at Wendell Berry and Stewart Brand.

Berry 's written a lot. The most recent anthologies of his non-fiction are The World-Ending Fire: The Essential Wendell Berry, and the Library of America's two volumes. (Vol.2-Essays 1993-2017)

Wendell Berry began his life in post-war America as the old times and the last of the old-time people were dying out, and continues to this day in the old ways: a team of work horses and a pencil are his preferred working tools. The writings gathered in The World-Ending Fire are the unique product of a life spent farming the fields of rural Kentucky with mules and horses, and of the rich, intimate knowledge of the land cultivated by this work. These are essays written in defiance of the false call to progress and in defense of local landscapes, essays that celebrate our cultural heritage, our history, and our home.

With grace and conviction, he shows that we simply cannot afford to succumb to the mass-produced madness that drives our global economy—the natural world will not survive it.

Yet he also shares with us a vision of consolation and of hope. We may be locked in an uneven struggle, but we can and must begin to treat our land, our neighbors, and ourselves with respect and care. As Berry urges, we must abandon arrogance and stand in awe.

“Wendell Berry’s formula for a good life and a good community is simple and pleasingly unoriginal. Slow down. Pay attention. Do good work. Love your neighbours. Love your place. Stay in your place. Settle for less, enjoy it more.” g'r

“Our understandable wish to preserve the planet must somehow be reduced to the scale of our competence - that is to wish to preserve all of its humble house - holds and neighbourhoods.”

“For agrarians, the correct response is to stand confidently on our fundamental premise, which is both democratic and ecological: the land is a gift of immeasurable value. If it is a gift, then it is a gift to all the living in all time. To withhold it from some is finally to destroy it for all. For a few powerful people to own or control it all, or decide its fate, is wrong.”

“Our human and earthly limits, properly understood, are not confinements but rather inducements to formal elaboration and elegance, to fullness of relationship and meaning.”

“And every day I am confronted by the question of what inheritance I will leave. What do I have that I am using up? For it has been our history that each generation in this place has been less welcome to it than the last. There has been less here for them. At each arrival there has been less fertility in the soil, and a larger inheritance of destructive precedent and shameful history.”

“the American Indian...knew how to live in the country without making violence the invariable mode of his relation to it; in fact, from the ecologist’s or the conservationist’s point of view, he did it no violence. This is because he had, in place of what we would call education, a fully integrated culture, the content of which was a highly complex sense of his dependence on the earth.”

- Is Berry's agrarian perspective relevant, given that most of us live urban lives (and probably should, from an environmentally-sustainable standpoint)?

- Does Berry's view of life as a gift exclude secularists who don't believe in a Giver?

Wendell Berry participated in this panel discussion as the 2012-2013 Avenali Chair in the Humanities at the Townsend Center for the Humanities, UC Berkeley. He was joined by UC Berkeley faculty panelists Michael Pollan (Graduate School of Journalism), Robert Hass (English), Miguel Altieri (Environmental Science, Policy and Management), and Anne-Lise Francois (English and Comparative Literature).

No comments:

Post a Comment